A history of the orchestra (3)

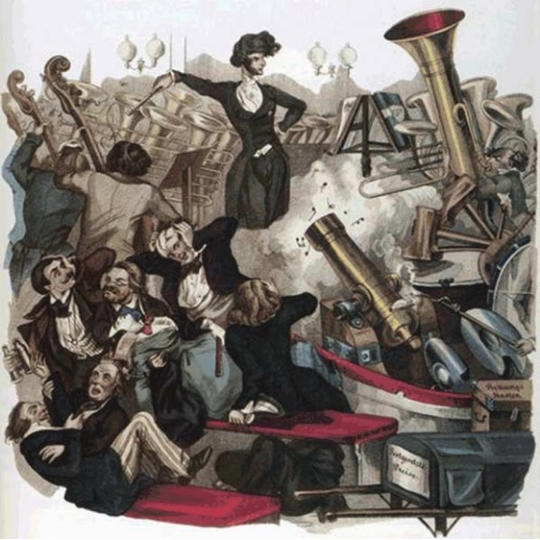

the orchestra in the 19th century The exclusive right to orchestral music the ruling elite in the 18th century possessed, is being broken in the 19th century. The French Revolution in particular played an important role in the changing political situation. Although the opera performances slowly became more accessible, the entrance fees were to high for the lower classes. The admission prices were high due to the costs for singers, theater agents, rental of the opera hall, stage clothing and set construction and in addition conductor and orchestra. The costs however for an instrumental concert, being costs for hall and orchestra with conductor only, would be considerably lower and so the admission prices. For a long time the concert programs will show these instrumental concerts to be considered a less costly substitute for the highly esteemed opera performances. The concerts took for instance as much time as an opera, that is a few hours. Generally one could enjoy two symphonies, two ouvertures, two major instrumental and four vocal pieces. This amount of music easily fills two concerts in our time. It turned out to be hard for the 19th century audience to get used to a purely instrumental concert. Proof is the tenacity that kept making all kinds of arias to be the highlights of the programs, despite the performance by often third-rate soloists. Gesellschaften and Societies Foundation for the organisation of these concerts were the “Concert Societies”. Being associations of music lovers, these Societies were by means of the contribution of their members able to rent halls or even to have them build. In these halls they organised socalled “subscription concerts” by orchestras and soloists they hired. Admission to the concerts was exclusively for members of the Society. A few of these societies are still in existence and famous, like the “Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde” in Vienna, - owner of the wellknown “Goldener Saal” -, the French “Société des Concerts” in Paris and the London “Royal Philharmonic Society”. The number of concert societies increased considerably between 1800 and 1850 leading to the construction of the first concert buildings, usually in modest proportions. The sheer novelty of all this is clearly illustrated by the reaction of a reporter at the opening of the concert hall of the Paris’ conservatoir in 1811. Bewildered he reports that: “ the orchestra has its place in the back like the actors in a theatre, although in every theatre the orchestra has its place in the middle between actors and audience.” Wagner wants a tuba The orchestra itself gradually will transform into the layout in which it still presents itself into the 20th century. The first half of the 19th century displays a rapid development of woodwind instruments and brass. This is caused by the improvement of the key mechanism for the woodwinds and the invention of the valve system for the brass instruments. For the first time woodwind and brass are technically equal members of the orchestra. The Romantic preference for timbre evokes the development of new wind instruments in the alto and tenor range, in the 18th century an open space as far as the wind instruments are concerned. Just a selection: the Basset horn, the Bass flute, Baryton oboe, Heckelphone, Sax tuba, Saxophone, English horn, Bass Clarinet and Contra Bassoon; only the last three instruments did ultimately get a place in the orchestra . you can’t oppose the brass In the middle of the century the brass instruments have a more or less permanent formation in the orchestra: four French horns, two or three trumpets, three trombones and one tuba. Wagner will later add his powerful “Wagner-tuba’s” to the brass. That’s why mainly composers writing in the second half of the 19th century, like Gustav Mahler and Bruckner, will make full use of this musical violence. Opposite the greatly increased volume of the brass there is for the sake of balance a steady growth in the number of strings: from less than 20 at the start of the19th century to an average of 40 or 50 strings by the middle. In 1846 Wagners orchestra in Dresden had 22 first and second violins, 8 altos, 7 celli en 6 double basses. The string instruments are however no longer the most imposing part of the orchestra, as in the 18th century: resistance is futile against the brass section operating on full strength. Next to the three timpani, customary around 1850, an extensive set of percussion instruments is being developed in the second half of the century. Hector Berlioz and Richard Strauss will make good use of it. an orchestra to dance The number and quality of the conservatoires are causing the steady increase of the technical ability of the musicians in the orchestra. From the start of the century the conductor is in charge of the orchestra, but no separate professional training for this responsible task will exist in this century. The course “orchestral conducting” was only in 1914 introduced at the Conservatoire in Paris. The most important positions were taken by conductors, who had emerged from the orchestra, only trained as an instrumentalist; perhaps the reason that conducting an orchestra a heavy burden was for many conductors. Their frustration appears from dozens of caricatures and lots of mockery in newspapers and magazines: “ A conductor is a kind of variety artist, doing an act by waving his arms, fluttering his hair, making dance steps and shaking his fists, an act accompanied by the orchestra”. Or the almost classical remark of “an inhabitant of the jungle”, for the first time in his life experiencing a concert by a symphonic orchestra: “Which surprised me the most, is the need of so many musicians to make just one man dance.” bigger is better One of the most characteristic features of the century of Romantism is perhaps the tendency to what could be called “gigantism”, the urge to make everything continuously and increasingly larger. As for the instruments: the “Octobasse” van Vuillaume makes his debut in 1849, an enormous double bass with a height exceeding three meters and 50 centimeters. In the same period two drums are build in England with a more than two meters diameter to be used at festivals. This “gigantism” can equally be found in the taste for huge numbers of musicians: Berlioz attempts to unite “all musical powers of Paris” and designs in 1844 an orchestra consisting 465 players, having 120 first, second, third and fourth violins. Also the nickname “Symphony of a Thousand ” for the 8th Symphony of Gustav Mahler is probably more the result of wishful thinking than of the seize of the required orchestra. The seize of the romantic compositions in general increases as well, even when omitting the enormous 19th century operas from the picture: An 18th century “sinfonia” by Johann Christiaan Bach for example has three parts and a duration of ten minutes. The 3th Symphony of Mahler has six parts and a duration of one hour and a half. The early 20th century will be particularly opposed to this last phenomenon. Rob van Haarlem “The History of the Orchestra” was published in the magazine of the symphony orchestra of Rotterdam called “Ouverture” in four parts between September 1975 en May 1976. It was reprinted in 1977 in the anniversary edition van “Klankbord”, the magazine of the Association of Dutch Orchestras. previous next