A history of the orchestra (4)

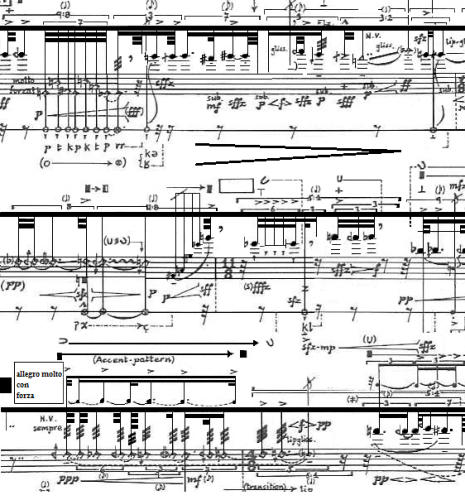

the orchestra in the 20th century At the beginning of the 20th century the symphonic orchestra was larger and more imposing than ever in its history. Due to the rapid development of the conservatoirs the skills of the members of the orchestra increased considerably and would keep doing so. The artistic level was taken care of by a new generation of conductors, leaving their own mark on the contemporary orchestral culture. Welknown are for instance Arturo Toscanini, Wilhelm Furtwängler and Willem Mengelberg from the first half and Herbert von Karajan and Karl Böhm from the second half of the century. In the early 20th century however resistance to the vast number of men in the orchestra and the overwhelming way the sound is poured out over the audience increases with young composers. In 1910 the young Viennese composer Anton Webern writes his “6 Stücke für Orchester Opus 6”, dedicated to his teacher Arnold Schönberg. In these Stücke he makes use of the orchestra in a way that will characterize the early part of the 20th century: No long melodies are recognisable in the music, but only short motivs, frequently no more than a dozen notes. Furthermore these short motivs are distributed over different instruments: the first four notes are for instance played by the flute followed by one note by the trumpet, four notes by the oboe and the last three by the horn. At no time the orchestra sounds in its entirety; only small groups of instruments, performing in often rather unusual combinations. This way of orchestrating takes away all sentiment from the music. The impression it makes on the audience is at first one of strange and incoherent music, but later on it has its own charm. music by machines Three years later a movement arises in Italy, seemingly threatening the established orchestras: the Italian Filippo Marinetti states in Le Figaro that music has to be “the mirror of life itself”. To achieve this ideal all the sounds of life together had to be the base of all music; sounds like streaming water, het rattle of engines, squeaking doors and the screaming of circular saw blades. On the 11th of August 1913 the first concert was given. The “orchestra” consisted of three buzzers, two clankers, one drone, three whistlers, two ruslers, two clocks, one ratchet, one sqeaker and last but not least one sniffer. The reception of the socalled “Bruïtism” was a bit mockingly and after the laughter died out the whole idea seemed doomed. But some distinguished composers adapted the concept that sound not made by musical instruments - commonly called “noise” -, could be music in given circumstances. So compositions were made having titles like “The Iron Foundry” by Alexander Mossolov (1927), “Machines agricoles” by Darius Milhaud en “Ballet Mécanique” by George Antheil. back from the iron foundry But the real breakthrough was the idea to use existing musical instruments to produce the noise intended; and percussion instruments appeared to be most suitable. The French composer Edgar Varèse was the first one to base his entire composition on instrumental sounds and noise. His famous “Ionisation” dating from 1931 is the first significant composition written for percussion only. It requires 41 percussion instruments, including piano and celesta. In addition to this small group of determined avant-gardists, there is a vast number of less extreme composers, using new insights at their own discretion, like Strawinsky, Bela Bartók en Darius Milhaud. Development stopped for a while caused by the cultural isolation Germany imposed on itself increasingly from 1933 and the growing political tension in the world. Once burst out, the Second World War will also take the life of Anton Webern. Everything comes to a halt until 1948. electrons make the music The second half of the 20th century has a tempestuous start: the newly developed possibilities to record and reproduce sound by electricity and the emerging computer put a brand new medium in the hands of the post-war generation of composers. A new kind of “graphic” score is devised, which will later also be used for instrumental music. In the fifties the emphasis is on electronic music, principally on the work by Karlheinz Stockhausen, partly produced in the Cologne Radio Studio. After 1960 again a search is made for possibilities in generating sound. Composers show great imagination in their struggle to create all kinds of noise: one German writer counted no less than 40 ways wind instruments had to be played in modern scores. Sometimes this creative freedom led to quite absurd situations when composers started issuing additional non-musical instructions. Especially in the sixties this often caused resentment to both the public and the musicians: when for instance in the slow part of the new Piano Concerto the pianist is seriously occupied reducing the Steinway Grand Piano - according to the score - to usable wood for the stove with the help of an axe (“Andante ma non troppo”), one can justly wonder to what extent music is still involved. Hiroshima from Poland Simultaneously some Eastern European composers wrote music that would become of great importance to the orchestra. György Ligeti composed in 1959 an innovative orchestral piece called “Atmosphères”. In this composition different kinds of noise, sometimes called “textures”, alternate and merge. Every texture is created by a specific combination of instruments. “Atmosphères” caused a sensation at his premiere. The strings are in the first half of the century frequently left out the compositions. Maybe thats why the Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki wrote in 1960 his “Threnos” voor 52 string instruments, dedicated to the many victims of Hiroshima. Characteristic are the intense and high pitched sound masses. Generally there is a growing interest in the second half of the 20th century in musical options offered by the classical symphonic orchestra, expanded with a extensive percussion group. The distance between composers, musicians and public seems to have diminished at the end of the seventies. The symphonic orchestra developed itself in the course of the twentieth century into a flexible and versatile musical medium with almost unlimited options. Rob van Haarlem “The History of the Orchestra” was published in the magazine of the symphony orchestra of Rotterdam called “Ouverture” in four parts between September 1975 en May 1976. It was reprinted in 1977 in the anniversary edition van “Klankbord”, the magazine of the Association of Dutch Orchestras. previous page top